How has the local renewable energy ordinance landscape changed since mid-2023, the last time we took stock of this fast-moving policy issue? It turns out a lot has happened since then. In our latest analysis, we address this question by summarizing the major trends across the Lower 48, including a comprehensive update of our local ordinance database.

According to our latest research findings, 975 counties across the continental United States now have some form of wind or solar restrictions in place. This is a significant increase from the end of 2023, when a total of 797 counties had instituted restrictive wind and solar ordinances. This represents a 22.3% increase in the number of counties that have passed (and in rare cases, updated) restrictive renewable ordinances during the intervening period between our analyses.

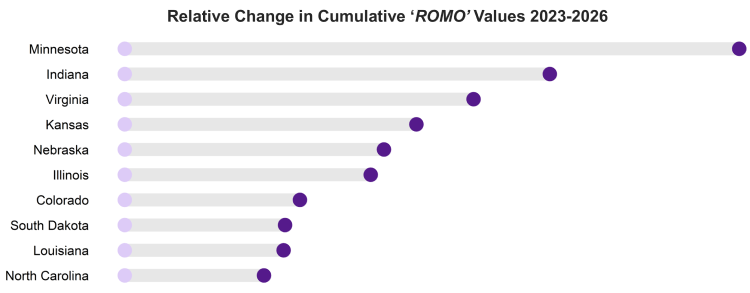

These changes have not been distributed evenly throughout the country. Regions like the Midwest, the Great Plains and Intermountain West, and Southeast show the biggest changes in terms of the number of counties with new ordinances, in combination with the stringency of such rules.

This is what the following figure shows, captured by the cumulative difference in our “Risk of Missing Out” (ROMO) index between 2023 and 2026. To clarify, the graph does not mean that states like Minnesota or Indiana are the most restrictive, but rather, they have seen the biggest changes over this time period. Our full analysis provides more detail, as well as the ability to search for individual counties and retrieve ordinance hyperlinks, as well as citations.

How can we explain these trends? Although the answer is undeniably complex and multi-causal, two milestones stand out as important pieces of the puzzle. The passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 made substantial funding available for developing clean energy infrastructure, which correlated with other political, economic, and social dynamics — including opposition from communities — that are part of the energy transition. The second election of President Donald Trump, with a clear anti-renewable and pro-fossil fuel agenda outlined in his own stated policy positions, as well as in Project 2025, introduced even more uncertainty to the system, empowering local anti-renewable interests in their efforts to oppose renewable siting.

These changes, however, must be understood in context. For example, the difference in cumulative ROMO scores above shows that many counties in Minnesota seem to be imposing onerous barriers to clean energy development. Understood in context, however, this is only partially true. After the passage of the IRA in 2022, many predominantly rural counties embarked on a push to regulate renewable development. Concomitantly, Minnesota passed legislation in 2024 allowing the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (PUC) to partially preempt local ordinances for large wind and solar energy infrastructure projects, allowing the state to oversee the entire permitting process. To understand how these ordinances may impact final siting decisions, we must also take state-level policies into account.

This update provides advocates, journalists, researchers, and county board officials with valuable information, in an open and accessible way. With it, we seek to empower stakeholders with critical data in our efforts to ensure that the clean energy transition not only happens, but that it does so consistent with just transition and energy democracy principles. To better understand the overall impact of the policies, as well as the magnitude of the changes experienced in the past few years, read the full analysis.