Governments and industries are "reopening" the economy while COVID-19 continues to rage across the United States. At the same time, the lack of effective, enforceable workplace health and safety standards puts workers and the general public at heightened risk of contracting the deadly virus. In a new report from the Center for Progressive Reform, Sidney Shapiro, Michael Duff, and I examine the threats, highlight industries at greatest risk, and offer recommendations to federal and state governments to better protect workers and the public.

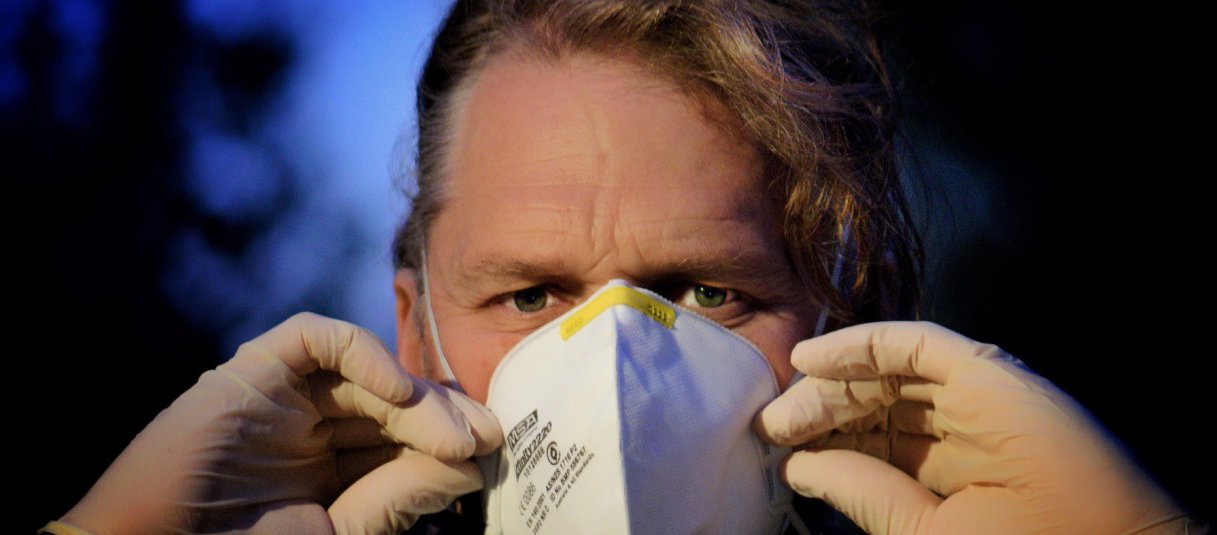

In many essential industries, the coronavirus risk is particularly acute because of the nature of the work and of the workplaces in which it is conducted. The lack of enforceable, pandemic-specific protections for workers and the hodgepodge of industry responses heighten this danger to workers. Industries affected range from health care to meatpacking, transportation to warehousing.

Heaping injustice on top of danger, coronavirus-related hazards fall disproportionately on Black, Latinx, and low-income workers – people whose economic circumstances and less reliable access to health care renders them all the more vulnerable. These workers are being treated as expendable, forced by the threat of losing their jobs to accept risks no member of Congress or White House staffer would accept for themselves or their families.

Whether federal and state governments ultimately heed the advice of public health experts to protect us all by better protecting worker health remains to be seen. Unfortunately, the Trump administration has largely failed to provide leadership and has instead used the pandemic as a rationale to roll back enforcement of existing workplace safety measures.

While the federal government has shown little interest in protecting workers from the coronavirus, we note that such leadership is not beyond its reach. Throughout Protecting Workers in a Pandemic: What the Federal Government Should Be Doing, my colleagues and I offer recommendations, some specific to preventing the spread of the virus, and some that apply the lessons of the pandemic to enduring workers’ rights issues.

These recommendations include:

While all of these recommendations focus on workers, the bottom line is that protecting worker health will better protect public health, especially in retail settings and other workplaces where customers, patients, and other members of the public have direct interactions with workers. To make this happen, OSHA and other federal agencies need to step forward, out of the background, and realign their operations to be more proactive, protective, and expedient. The American people deserve nothing less.

Help us spread the word about this report on Twitter and Facebook.

Showing 2,942 results

Thomas McGarity | June 17, 2020

Governments and industries are "reopening" the economy while COVID-19 continues to rage across the United States. At the same time, the lack of effective, enforceable workplace health and safety standards puts workers and the general public at heightened risk of contracting the deadly virus. In a new report from the Center for Progressive Reform, Sidney Shapiro, Michael Duff, and I examine the threats, highlight industries at greatest risk, and offer recommendations to federal and state governments to better protect workers and the public.

Katlyn Schmitt | June 16, 2020

On June 9, the House Energy and Commerce Committee's Subcommittee on Environment and Climate Change held a remote hearing, “Pollution and Pandemics: COVID-19’s Disproportionate Impact on Environmental Justice Communities.” The Center for Progressive Reform, joined by Fair Farms, Sentinels of Eastern Shore Health (SESH), and the Sussex Health and Environmental Network submitted a fact sheet to subcommittee members outlining the impacts of COVID-19 on the Delmarva Peninsula, along with a number of recommendations for building a more sustainable model for the region. The area is home to a massive poultry industry, hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic. We addressed several of the most severe problems in our fact sheet.

Michael C. Duff | June 15, 2020

While I suspect that workers' compensation claims, even without the aid of workers' compensation causation presumptions, may fare better than some actuaries suspected (preliminary scuttlebutt of about a 40 percent success rate is higher than I expected), there is no reasonable doubt that large numbers of workers will ultimately go uncovered under workers' compensation during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Katlyn Schmitt, William Andreen | June 11, 2020

We are five years out from the final 2025 deadline for the Chesapeake Bay cleanup agreement, known as the Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL). With the approval of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), each of the Bay states has finalized the three required phases of their Watershed Implementation Plans (WIPs). This month, those states have released their draft 2020-2021 milestones, which, when final, will set out the key short-term goals states will work toward, stepping up their restoration work so that they can stay on track to meet their final 2025 pollution reduction goals.

Brian Gumm, Katie Tracy | June 11, 2020

In a June 11 order, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals denied an AFL-CIO writ of mandamus asking the court to compel the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to do more to protect workers from infectious diseases, such as COVID-19. The order continues the dangerous status quo of workers laboring with no enforceable protections from the highly contagious and deadly virus.

Alice Kaswan | June 10, 2020

Black lives matter. As we contemplate the scope of structural racism, we find that “Black Lives Matter” needs to be said over and over again. We say it as we push for policing that protects rather than threatens. And we can keep saying it. Like when we talk about having available, affordable health care. Having access to technology and broadband, a quiet space, and time when the classroom becomes off limits due to a pandemic or climate-driven extreme weather. Finding an affordable place to live and landlords who don’t discriminate. Finding meaningful work and getting a promotion. Finding fresh food. Getting respect. And then there’s the environment. We still see stark disparities in exposures to environmental harms in our country.

Darya Minovi | June 9, 2020

June 1 marked the start of hurricane season for the Atlantic Basin. While not welcome, tropical storms, strong winds, and storm surges are an inevitable fact of life for many residents of the Eastern Seaboard and the Gulf Coast. As a new paper from the Center for Progressive Reform explains, with those storms can come preventable toxic flooding with public health consequences that are difficult to predict or control.

Michael C. Duff | June 3, 2020

For decades, commentators have complained about how long it can take for workers attempting to unionize to simply get an election in which workers make an up-or-down decision on whether to form a union. For many years, employers were able to raise hyper-formalistic legal arguments that took so long to resolve that the employees initially interested in forming a union had often moved on to other employment. In far too many cases, employers also unlawfully coerce workers during the delay, and those workers eventually withdraw their support for the union. After much internal wrangling, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) enacted a series of new election procedures in 2014, but after Donald Trump took office, the Board published a “Request for Information” in December 2017 that implicitly questioned the continuing need for, and efficacy of, a rule that was little more than two years old.

Katlyn Schmitt | June 2, 2020

In April, the U.S. Supreme Court finally weighed in with an answer to a longstanding question about what kinds of pollution discharges rise to the level of a "point source" and require a permit under the Clean Water Act. The Court dipped its toes into some muddied waters, as this question has been the subject of a range of decisions in the lower courts for decades, with little consensus. Panelists on the Center for Progressive Reform's May 28 clean water webinar examined the Supreme Court's opinion and its possible implications for water quality protections.