This post was originally published on Legal Planet. Reprinted with permission.

The world’s ecosystems have been subject to an increasingly dangerous cocktail of stressors from land and ocean over-development, invasive species, and pollution. But rather than stem the tide of these harms, the Trump administration has resurrected several regulatory changes to the Endangered Species Act designed to stifle species’ protections and provide land developers even more power to destroy invaluable ecosystems.

Unlawful Changes to the Endangered Species Act

These proposed amendments are as irresponsible as they are illegal. To start, they allow the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to consider economic impacts in decisions about whether a species should be listed as endangered. That may sound reasonable at first, but the law is clear — it is inappropriate to consider economic factors in a scientific determination. Agency regulations have long underscored that listing decisions must be made “without reference to possible economic or other impacts” since Congress passed the Endangered Species Act in 1973.

The proposed changes also authorize the Fish and Wildlife Service to consider national security and economic factors when it determines if a territory is critical for the survival of a listed species — the first time it would be allowed to do so. This is illegal: the Endangered Species Act plainly directs the Fish and Wildlife Service to decide what species are in danger of extinction and to designate habitats critical to their survival. Congress understood even 52 years ago that those are biological questions, for which economic costs are irrelevant.

The proposed changes also eliminate default protections for species newly listed as threatened (current examples are the grizzly bear or monarch butterfly). That would mean that such species get zero protection under federal legislation unless the Fish and Wildlife Service decides to adopt protections applicable only to that species. And even then, the protections would usually be weaker than those for endangered species.

These proposed changes exacerbate other recent proposals that will further imperil our nation’s fragile ecosystems. Under the Endangered Species Act, it is illegal to “harm” a protected species. Until now, the definition of such harm, which the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld, includes any significant habitat modification that kills or injures wildlife.

A pending regulatory proposal would upend that definition and hold that many habitat modifications that kill or injure a listed species aren’t harmful. Needless to say, this change threatens to cause widespread, long-lasting, detrimental impacts to imperiled species across the country.

Proposals Harm Biodiversity, the Government, and the Economy

Collectively, these actions lay bare that the Trump administration doesn’t care about species conservation. In fact, the most recent proposals are largely the same narrow-minded ones offered the last time Trump was in the White House.

At the very least, the proposals are a waste of public money. The changes at a minimum will be tangled up in litigation for years. Courts will also likely overturn them, as they did the last time they were proposed.

But more alarmingly, the proposals show that the Trump administration is gambling with future generations of countless plants, animals and, yes, humanity, for the short-term gain of a few real estate developers.

Nor do these changes reflect what the American public wants. Since its enactment in 1973, surveys have shown consistent, unyielding public support for the Endangered Species Act. Such approval is not surprising. Every year the legislation supports over $1 trillion in ecological, economic, and other benefits that dwarf its costs.

And while the legislation is far from perfect, it has saved 99 percent of species protected by the law from extinction — some 227 species that include gray whales and peregrine falcons. Nearly half of at-risk species have stabilized or improved under the law’s protection. Another 60 have recovered enough to be de-listed. In short, even though the law is shamefully underfunded, it has been an enormous success.

Undoubtedly, the ESA could be more effective at promoting conservation. What is needed to improve it is largely common sense. Protect sensitive habitat. Help vulnerable species and ecosystems contend with conservation threats and adapt to changing conditions. Adequately fund starved agencies to ensure the law and other conservation laws are implemented, enforced, and updated to deal with new harms like global climate change.

But the Trump administration is not interested in safeguarding virtually anything of collective importance — our dwindling natural resources, our immediate economic prosperity, or the ecological heritage that the overwhelming majority of Americans believe we owe future generations.

Showing 2,943 results

Alejandro Camacho | January 27, 2026

The world’s ecosystems have been subject to an increasingly dangerous cocktail of stressors from land and ocean over-development, invasive species, and pollution. But rather than stem the tide of these harms, the Trump administration has resurrected several regulatory changes to the Endangered Species Act designed to stifle species’ protections and provide land developers even more power to destroy invaluable ecosystems.

Daniel Farber | January 26, 2026

At its core, the unitary executive theory (UET) says that the president can fire anyone in the executive branch for any reason or no reason. Although the UET purports to be based on originalism, it has become clear that the U.S. Supreme Court has no interest at all in examining the history. Supreme Court conservatives think complete presidential control is simply the ideal way to run the government. The deep flaws in that theory are now becoming apparent.

Daniel Farber | January 9, 2026

In 2025, President Donald Trump rolled out new initiatives at a dizzying rate. That story, in one form or another, dominated the news. This year, much of the news will again be about Trump, but he will have less control of the narrative. Legal and political responses to Trump will play a greater role, as will economic developments. Trump’s anti-environmental crusade may run into strong headwinds.

Hannah Wiseman, Seth Blumsack | December 15, 2025

As projections of U.S. electricity demand rise sharply, President Donald Trump is looking to coal – historically a dominant force in the U.S. energy economy – as a key part of the solution. In an April 2025 executive order, for instance, Trump used emergency powers to direct the Department of Energy to order the owners of coal-fired power plants that were slated to be shut down to keep the plants running. But there remain limits to the president’s power to slow the declining use of coal in the U.S.

Daniel Farber | December 11, 2025

A recent U.S. Office of Management and Budget (OMB) memo proclaimed the Trump administration’s commitment to “deregulating at an unprecedented scale.” To advance that agenda, the memo tells agencies to put a thumb on the scale in favor of rollbacks. In contrast, most lawyers and economists would say that regulation and deregulation are subject to the same rules. Sometimes, the conventional wisdom is right.

Madison Condon | December 3, 2025

In Free Gifts, Alyssa Battistoni traces the concept of the “externality” across the past century. This history begins in 1920, when the economist Alfred Pigou observed how private market transactions could impose uncompensated harms on third parties, such that the prices of goods failed to reflect their true (social) cost. Fortunately, he argued, these external costs could be rectified by government intervention: adding a tax equal to the social cost, which would cause market trading to “internalize” the harm and produce the optimum amount of the activity in question. Free-market advocates viewed such externalities as a rare exception to the general rule of the wisdom of the market. As Battistoni describes, however, this would change in the coming decades.

Sophie Loeb | December 2, 2025

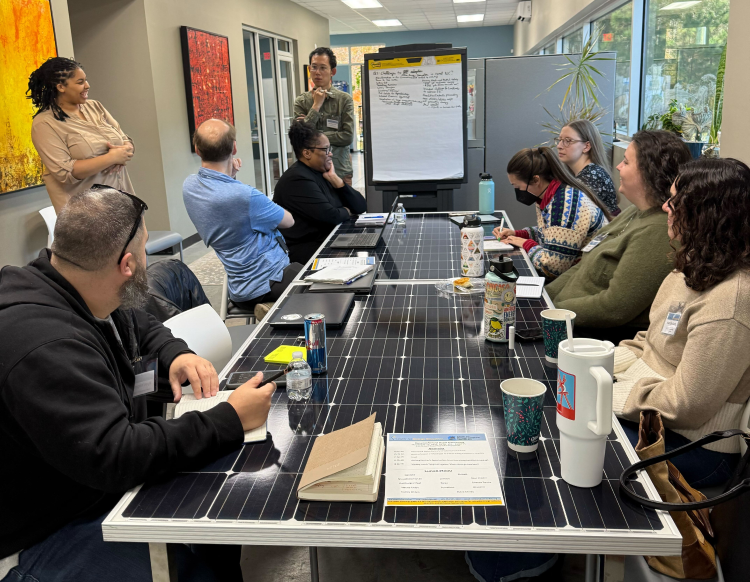

On November 13, 20 folks attended the second annual rural clean energy convening in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, co-sponsored by the Center for Progressive Reform and the Center for Energy Education. Attendees included academics, energy policy advocates, small-scale developers, technical experts, and government representatives. We built off last year’s convening, addressing the new North Carolina policy landscape and context given the repeal of federal funding, the state’s proposed unfavorable carbon plan, and rising energy burden in communities.

Rachel Mayo | November 25, 2025

This November, we honor the leadership, knowledge, and resilience of America’s first peoples, who have safeguarded the land, water, and air that sustain us all.

Daniel Farber | November 13, 2025

Although Congress vetoed California’s most recent vehicle regulations, the state can pass new regulations so long as there are significant differences from the ones Congress overturned. The Trump administration has been arguing all along that California lacks the power to regulate greenhouse gases from vehicles. Those regulations are a crucial part of the state’s climate policy. Sooner or later, courts will need to decide the extent of California’s legal authority over vehicle emissions. The issues are complex, involving an unusual statutory scheme. Here’s what you need to know, and why I think California should win this fight.